--

| Index |

BENJ. F. TAYLOR,

AUTHOR OF "SONGS OF YESTERDAY," "OLD-TIME PICTURES," "WORLD ON

WHEELS," "CAMP AND FIELD" ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

CHICAGO:

S. C. G-RIGGS AND COMPANY.

1878.

MRS. MARY SCRANTON BRADFORD,

OF CLEVELAND, OHIO,

WHOSE DAILY DEEDS OF NOBLE KINDNESS HAVE

BRIGHTENED MANY A LIFE AND BEAUTIFIED

HER OWN, THIS BOOK OF DAYS OF

SUNSHINE IS AFFECTIONATELY

INSCRIBED BY HER

RELATIVE AND FRIEND.

CONFIDENTIAL.

THE only care-free, cloudless summer of my life, since childhood, was spent in California. The going there was a delight, and the leaving there a regret.

This gypsy of a book has few facts and not a word of fiction; not so much as a dry fagot of statistics or a wing-feather of a fancy.

" How do you like California?" was the daily question, and to the uniform reply came the quick rejoinder: "Ah, but you should see it in the winter, for the summer is in the winter."

The writer sympathizes with any reader who misses what he seeks in this small volume, and can only soften " the winter of our discontent" by saying: Ah, but you should know "what pain it was to drown" what had to be omitted!

Perhaps we two may meet again in the groves of Los Angeles, when the oranges are in the gold and the almond blossoms shine.

CONTENTS.

OVERLAND TRAIN

" SET SAIL"

PREFACE. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II.

FROM VALLEY TO MOUNTAIN -

CHAPTER III.

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CANON -

CHAPTER IV.

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN

CHAPTER V.

FROM WINTER TO SUMMER

CHAPTER VI.

SAN FRANCISCO STREET SCENES

CHAPTER VII.

THE ANIMAL, MAN - -

"John," the Heathen

" Hoodlum," the Christian Picnics - -

|

6 CONTENTS. |

|

|

CHAPTER VIII. |

|

|

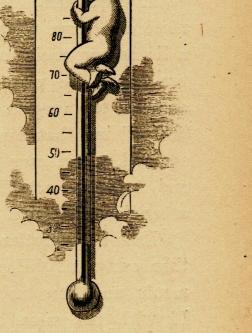

COAST, FORTY-NINERS AND CLIMATE - - |

- 94 |

|

The Pacific Breezes - |

- 101 |

|

Weather on Man - - |

- 103 |

|

_ CHAPTER 1X. |

|

|

GOING TO CHINA - - •• - |

- 106 |

|

A Chinese Restaurant - - |

108 |

|

" We'll All Take Tea" |

- 109 |

|

The Joss-House and the Gods |

110 |

|

"Twelve Packs in his Sleeve" |

114 |

|

An Opium Den - |

115 |

|

The Opium-Smoker's Dream - |

- 116 |

|

"The Royal China Theatre" - |

- 118 |

|

"The Play's the Thing" - - |

- 119 |

|

The Orchestra - - |

- 121 |

|

CHAPTER X. |

|

|

MISSION DOLORES AND THE SAINTS - - |

- 124 |

|

The Old Graveyard |

126 |

|

The Saints - |

- 128 |

|

CHAPTER XI. |

|

|

VALLEY RAMBLES AND A CLIMB - - |

- 131 |

|

A Dead Lift at a Live Weight |

133 |

|

On the High Seas |

140 |

|

The Hog's Back - - - |

143 |

|

CHAPTER XII. |

|

|

THE GEYSERS |

- 146 |

|

CHAPTER XIII. |

|

|

THE PETRIFIED FOREST - - - - |

156 |

CONTENTS. 7

CHAPTER XIV.

HIGHER AND FIRE

CHAPTER XV.

A MINT OF MONEY

Aladdin's Cave

Is it Worth it - Washing-Day

Midas's Kitchen - Bricks and Hoop-Poles Weighing Live Stock "The Golden Dustman"

CHAPTER XVI.

BOUND FOR THE YO SEMITE -

Taking a Mountain A Mountain Choir

"The Ayes Have It" Down the Mountains The Big Trees -

A Forest Ride -

First Glimpse of the Yo Semite Through the Valley - The Grand Register -

El Capitan - The Bridal Veil

Mirror Lake

Up a Trail

Yo Semite Fall and Sun Time Breaking up Camp -

166

174 177 180 182 183 184 189 190

192 200 201 ' 202 203 205 209 210 214 217 221 222 224 227 232 236

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER XVII. WHALES, LIONS AND WAR DOGS

Seals - - The Golden Gate

CHAPTER XVIII. A TRIP TO THE TROPIC

A Difficult Sunrise

The Tehachapi Love-Knot

The Mojave Desert A Vegetable Acrobat

The Mirage - -

The City of the Angels The Orange Groves The Vineyards

"A Bee Ranch" -

The Mission of San Gabriel

The Garden -

CHAPTER XIX. KINGS OF SOCIETY

Latitudes -

The Spirit of California The Men and Women Home Again -

BETWEEN THE GATES.

OVERLAND TRAIN.

1.

FROM Hell Gate to Gold Gate FROM

the Sabbath unbroken, A sweep continental

And the Saxon yet spoken!

By seas with no tears in them,

Fresh and sweet as Spring rains,

By seas with no fears in them,

God's garmented plains,

Where deserts lie down in the prairies' broad calms, Where lake links to lake like the music of psalms.

II.

Meeting rivers bound East

Like the shadows at night,

Chasing rivers bound West

Like the break-of-day light,

Crossing rivers bound South

From dead winter to June,

From the marble-old snows

To perennial noon — Cosmopolitan rivers, Mississippi, Missouri,

That travel the planet like Jordan through Jewry.

9

OVERLAND TRAIN. 11

And this world glancing back with a colorless face. Who marvels Mount Sinai was the State House of God? Who wonders the Sermon down old Galilee flowed? That the Father and Son each hallowed a height Where the lightnings were red and the roses were white! Oh, Mountains that lift us to the realm of the Throne, A Sabbath-day's journey without leaving our own, All day ye have cumbered and beclouded the West, Low glooming, high looming, like a storm at its best, By distance struck speechless and the thunder at rest.

v.

All day and all night

It is rattle and clank, All night and all day

Smiting space in the flank,

And no token those clouds Will ever break rank. Still the engines' bright arms

Are bared to the shoulder

In the long level pull

Till the mountains grow bolder.

Ah! we strike the up grade!

We are climbing the world!

And it rallies the soul

Like volcanoes unfurled,

Where it looks like the cloud that led Moses of old, And the pillar of fire born and wove in one fold From the womb and the loom of abysses untold.

12 BETWEEN THE GATES.

VI.

We strike the Great Desert

With its wilderness howl, With its cactus and sage,

With its serpent and owl, And its pools of dead water,

Its torpid old streams, The corpse of an earth

And the nightmare of dreams;

And the dim rusty trail

Of the old Forty-nine,

That they wore as they went

To the mountain and mine,

With graves for their milestones;

How slowly they crept,

Like the shade on a dial

Where the sun never slept,

But unwinking, unblinking, from his quiver of ire Like a desolate besom the wilderness swept

With his arrows of fire.

VII.

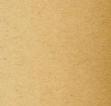

Now we pull up the globe! It is grander than flying, 'Mid glimpses of wonder that are grander than dying, Through the gloomy arcades shedding winter and drift, By the bastions and towers of omnipotent lift, Through tunnels of thunder with a long sullen roar, Night ever at home and grim Death at the door.

We swing round a headland,

Ah! the track is not there!

OVERLAND TRAIN. 13

It has melted away

Like a rainbow in air!

Man the brakes! Hold her hard! We are leaving the world!

Red flag and red lantern unlighted and furled.

Lo, the earth has gone down like the set of the sun—Broad rivers unraveled turn to rills as they run—Great monarchs of forest dwindle feeble and old — Wide fields flock together like the lambs in a fold — Yon head-stone a snow-flake lost out of the sky That lingered behind when some winter went by!

Ah, we creep round a ledge

On the world's very edge,

On a shelf of the rock

Where an eagle might nest,

And the heart's double knock

Dies away in the breast

We have rounded Cape Horn! Grand Pacific, good morn!

VIII.

Now the world slopes away to the afternoon sun — Steady one! Steady all! The down grade has begun. Let the engines take breath, they have nothing to do, For the law that swings worlds will whirl the train

through.

Streams of fire from the wheels,

Like flashes from fountains;

And the dizzy train reels

As it swoops down the mountains : And fiercer and faster

14 BETWEEN THE GATES.

As if demons drove tandem

Engines "Death" and "Disaster!"

From dumb Winter to Spring in one wonderful hour; From. Nevada's white wing to Creation in flower! December at morning tossing wild in its might—A June without warning and blown roses at night!

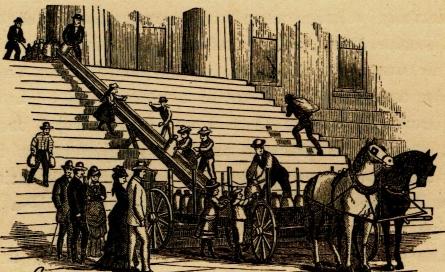

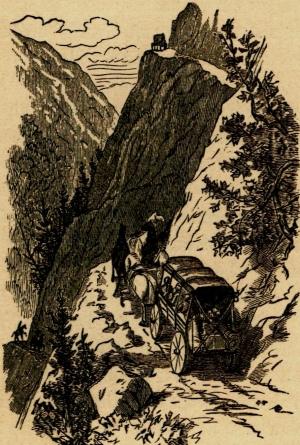

DOUBLING CAPE HOBN.

Above us are snow-drifts a hundred years old, Behind us are placers with their pockets of gold, And mountains of bullion that would whiten a noon, That would silver the face of the Harvesters' moon. Around us are vineyards with their jewels and gems,

OVERLAND TRAIN. 15

Living trinkets of wine blushing warm on the stems, And the leaves all afire

With the purple of Tyre.

Beyond us are oceans of ripple and gold,

Where the bread cast abroad rolls a myriad fold—Seas of grain and of answer to the prayer of mankind, And the orange in blossom makes a bride of the wind, And the almond tree shines like a Scripture in bloom, And the bees are abroad with their blunder and boom — Never blunder amiss, for there's something to kiss Where the flowers out-of-doors can smile in all weather, And bud, blossom and fruit grace the gardens together. Thereaway to the South, without fences and bars, Flocks freckle the plains like the thick of the stars; Hereaway to the North, a magnificent wild,

With dimples of canons, as if Universe smiled. Ah! valleys of Vision,

Delectable Mountains

As grand as old Bunyan's,

And opals of fountains,

And garnets of landscapes,

And sapphires of skies,

Where through agates of clouds

Shine the diamond eyes.

Ix.

We die out of Winter in the flash of an eye,

Into Eden of earth, into Heaven of sky;

Sacramento's fair vale with its parlors of God,

Where the souls of the flowers rise and drift all abroad,

16 BETWEEN THE GATES.

As if resurrection were all the year round

And the writing of Christ sprang alive from the ground, When He said to the woman those words that will last When the globe shall grow human with the dead it has

clasped.

Live-oaks in their orchards, rare exotics run wild, No orphan among them, each Nature's own child. Oh, wonderful land where the turbulent sand

Will burst into bloom at the touch of a hand,

And a destrt baptized

Prove an Eden disguised.

x.

There's a breath from Japan

Of an ocean-born air, Like the blue-water smell

In an Argonaut's hair! 'Tis a carol of joy

With a sweep wild and free;

And the mountains deploy

Round the Queen of the West,

Where she sits by the sea—By the Occident sea

In her Orient vest, Babel Earth at her knee, And the heart of all nations

Alive in her breast—Where she sits by the Gate

With its lintels of rock,

And the key in the lock—

17

OVERLAND TRAIN.

By the Lord's Golden Gate,

With its crystal-floored chamber,

And its threshold of amber,

Where encamped like a king,

The broad world on the wing, Her grand will can await. Where now are the dunes, The tawny half-moons

Of the sands ever drifting, Of the sands ever sifting, By the shore and the sweep Of the sea in its sleep? Where now are the tents,

With their stains and their rents. All landward and seaward

Like white butterflies blown? All drifted to leeward,

All scattered and gone. And this uttermost post

Of earth's end is the throne Of the Queen- of the Coast, Who has loosened her robe And girdled the globe

With her radiant zone—The throb of her pulses

Has fevered the Age—She has silvered and gilded

All history's page!

She has spoken mankind, 1*

18 BETWEEN THE GATES.

And has uttered her ships Like the eloquent words

From most eloquent lips — They have flown all abroad Like the angels of God! Sails fleck the world's waters

All bound for the Gate, All their bows to the Bay,

Like the finger of Fate. Child of the wilderness

By deserts confined,

Wide waters before her,

Wild mountains behind, She unlocks her treasures

To the gaze of mankind.

Her name is translated into each human tongue,

Her fame round the curve of the planet is sung,

And she thinks through its swerve By the telegraph nerve.

%I.

When the leaf of the mulberry is spun into thread, Then the spinner is shrouded and the weaver is dead; And that shroud is unwound by the fingers of girls, And the films of pale gold clasp the spool as it whirls,

As it ripens and rounds

Like some exquisite fruit

In the tropical bounds,

In air sweet as a lute,

Till the shroud and the tomb,

OVERLAND TRAIN. 19

Dyed in rainbow and bloom, Glisten forth from the loom Into garments of pride, Into robes for a bride,

Into lace-woven air

That an angel might wear. Ah! marvelous space

'Twixt the leaf and the lace, From the mulberry worm To the magical grace

Of the fabric and form! Oh, Imperial State,

Splendid empire in leaf,

That grows grand on the way

To the sky and the day, Like the coralline reef

To be royally great.

Dead gold is barbaric, but its threads can be woven

Into harmonies fine, like the tones of Beethoven, Can be raveled and wrought

Into love-knots of faith

For the daughters of Ruth—Into garments of thought,

Into pinions for truth —

And be turned from the wraith

Of a misty ideal

That may vanish in night, To things royal and real That shall live out the light.

20 BETWEEN THE GATES.

So the true golden days

Shall be kindled at last, And this realm shall rule on When the twilights are gone, In the grandeur of truth And the beauty of youth's

Till long ages have passed!

ON a bright Spring morning we set sail from Chicago for the Golden Gate. Nothing on solid land is the twin of an ocean voyage but a trans-continental trip by rail. There is a sort of through" look about Pacific-bound passengers. The shaggy blanket; the bruin of an overcoat; the valise not black and glossy, but the color of a sea-lion; the William Penn of a hat, broad as to its brim as the phylacteries of the Pharisees; the ticket that shuts over and over like a Chinese book; the capacious lunch basket where, amid sardines, cheese; dried beef, bread, pickles and pots of butter, protrude bottles with slender necks like Mary's, Queen of Scots, and young teapots with impudent noses; the settling into place like geese for a three-weeks' anchorage—all these betoken, not a flitting, but a flight.

The splendid train of the Chicago and Northwestern road, that controls a line of more than three thousand miles, and traverses six states and territories, steams out of the "Garden City's" ragged edges that refine and soften away into rural scenes, and meets many a lovely village hurrying toward the town. It rings its brazen clangor of salute. Shrubbery and stations clear the way. The horizons curve broadly out. We are fairly at sea amid the rolling glory of Illinois. The eastward world

21

22 BETWEEN THE GATES.

slips away beneath the wheels, like the white wake at a schooner's heels.

And then I think of another day in the year '49, and the stormy month of' March, when the tatters of white winter half-hid earth's chilly nakedness, and Euroclydon blew out of the keen East like the King's trumpeter, and a little procession of wagons was drawn up facing West on Lake street, Chicago, and daring fellows were snapping revolvers and casing rifles, and making ready for the long, dim trail through wilderness, desert and canon, through delay, danger and darkness—a trail drawn across the continent like the tremulous writing of a death-warrant when Mercy holds the pen. The horses' heads were toward the sunset, and the stalwart boys were ready, the gold-seekers of the early day. There were women on the sidewalks, there were children lifted in men's stout arms that might never clasp them more.

The captain gave the word, and the cavalcade drew slowly out, the last canvas-covered wain dwindled to an ant's white egg, and the pioneers were gone; gone into a silence as profound as the grave's. Spring should come and go, June should shed its roses, autumn roll its golden sea and break into the barn's broad bays in the high-tides of abundance; the winter fires should glow again, and yet no word from the Argonauts, no lock from the Golden Fleece of the new-found El Dorado of the farthest West. Ah, the weary waitings, the hopes deferred, the letters soiled and wrinkled and old, that crept by returning trains, or doubled the Cape or crossed the Isthmus, that the readers thanked God for and took courage, be-cause the writers were not dead last year.

And now it is a six days' sweep as on wings of eagles

"SET SAIL." 23

from the Prairies of Garden Gate to Pacific's Golden Gate! Verily Galileo's whisper has swelled to a joyful shout: "THE WORLD MOVES!" Fox river, Rock river, Mississippi, the old Father of them all, are crossed in one sunshine. The Cedar is reached by tea-time ; we are riding the breezy swells of Iowa; the second morning finds us giving Council Bluffs a cold shoulder, and making for " The Big Muddy," which is the prose for that ancient maiden, Missouri. Council Bluffs is the old Ranesville, where the Mormons advanced the first parallel in their long siege to take the parched desert of Utah, with its strange mimicry of the salted ocean that slakes no thirst, and to make a blooming garden with streams of living water.

Omaha goes between wind and water, a bad region for a solid shot to strike a ship, but a good thing for a town. It was the base of supplies for the bearded mountain-men who bundled their furs down to the river. It was the point of departure for the Pike's Peakers and the caravans " Frisco "-bound. It has hot water on both sides of it, from ocean to ocean. It has cold water, such as it is, "slab and good," like witches' broth, in the Missouri that, allied with the Mississippi, flows from the regions of the rude North, up the round world to the Gulf of Mexico and the sea. And it has wind. Caves (f 1Eolus! How it blows! If the wild asses of Scripture times could live on the East wind, they would fairly fat-ten on the Zephyrs of Omaha.

The bridge over the Missouri, swung in the air like a rainbow with no colors in it, and almost three thousand feet long, is a great gateway to the West. It has triumphed over the uneasiest sands that ever slipped 'out from under a foundation, and the worst river to drown

24 BETWEEN THE GATES.

geographies that ever went anywhere. I have crossed that river in _a stage-coach, in a boat, and on foot. It gets up and lies down in a new place oftener than any other running water in America. It changes beds like a fidgety man in a sultry night. It is as worthless for a boundary-line as a clothes-line. It has been known to slice out an Iowa county-seat, and leave it within the limits of Nebraska, as a sort of lawyer's lunch, to be wrangled over.

Fort Calhoun, some two hours' drive up the river from Omaha, is the point whence Lewis and Clark set forth, seventy-three years ago, into a wilderness that howled, and discovered that great watery trident of the Columbia, and named it Lewis, Clark and Multnomah. A while ago I visited the Fort, and the stump of the flag-staff yet remained whence the old colors drifted out in the morning light, when the Discoverers set forth. In their day the Fort stood on the river's bank, and in case of in-vestment from the landward side, water could be drawn up in buckets from the Missouri, and so they wet their throats and kept their powder dry. In my day, I looked from the old site upon a forest of cottonwoods about a Sabbath-day's journey in breadth! That river had gotten up and lain down again at a quiet and comfortable distance from the click of locks and clank of scabbards. What it will do next nobody can tell.

The Union Pacific train is just ready to move out. The bright-hued cars of the Northwestern are succeeded by the soberly-painted coaches of the Union Pacific. They have taken the tint of ocean-going steamers. Men and women are bundling aboard with bags and baskets. The spacious Depot is thronged with crowds in motley wear.

"SET SAIL." 25

A breeze draws through the great building like the blast of a furnace. .At one hawk-like swoop it catches up a woman's bonnet and dishevels her head, and blows her

ticket out at one door

while her urchin of a boy trundles out at another. Her desperation is logical. She grasps for the hat, plunges for the ticket, and proceeds to look up the baby. Let no indignant matron deny the soft impeachment. The fact remains: bon-net, ticket, baby.

Here, a Norwe-

gian sits upon a I °4Poq,c

knapsack colored like rr

an alligator, his leather breeches polished as a razor-strap, and his hair gone to seed. There, an Indian with his capillary midnight flowing down each side of his oleaginous face, as if he had ambushed in a horse's tail and forgot his body was in sight.

Yonder, a pair of Saxons just escaped from a band-box, fit for the shady side of Broadway, but not for the long trail.

Now, an Englishman in tweed, and sensible shoes with soles as thick as a shortcake, an inevitable white bat, and a vest that nobody would think of asking him to " pull 'down," for a little more waistcoat, and pantaloons could

2

26 BETWEEN THE GATES.

go out of fashion. Then, a girl with .a portfolio in a strap, who means to be " a chiel amang us takin' notes," when she ought to be using her bright eyes and giving " Faber No. 2 " a blessed rest.

The Depot bubbles and boils like a caldron. The engine backs, clanging down with a cloud and a rush. People climb on and climb off the laden cars crazier than ever. They are giving old ladies a lift from behind. They are tugging up carpet-bags like cats with their last kittens. They are all colors with excitement and hurry. It strikes you queerly that everybody is going, and no-body is staying. The demon of unrest is the reigning king. "Long live the king!" for life is motion. Still life is death's first cousin. A Babel of trunks is surging toward the baggage-cars. Trucks are piled like dromedaries. There's the Saratoga that might be lived in if it only had a chimney, and the iron-bound chest of the mistletoe-bough tragedy, and the dapper satchel as sleek and black as a wet mink, and the little brindled hair-trunk with its brazen lettering of nail-heads, and the canvas sack as rusty as an elephant. And so they tumble aboard with an infinite jingle of checks; an acrobatic, jolly troop, the heart's delight of the trunk-makers. You see your own property, bought new for the occasion, rolling over and over corner-wise like a possessed porpoise. Alas, for any pigments or unguents or dilutions or perfumes that may break loose in that somerset, and make colored maps of the five continents upon your wedding vest or your snowy wrapper. Last, the leathern purses of the United States Mail fly from the red wagons like chaff from a fanning-mill. The engine's steam and impatience are blown off in a whistle together. It spits

"SET SAIL." 27

spitefully on one side and the other, like a schoolboy out of the corners of his mouth.

And amid the whirl of the Maelstrom—for if Nor-way has none, at least Omaha has one—there are only two living things that are quiet and serene. The one is a youthful descendant of Ham, with a heel like the head of a clawhammer—five claws instead of a pair—lying on a truck upon a stomach that, like an angleworm's, pervades the whole physical man, and the descendant turned up at both ends, like a rampant mud-turtle, his mouth full of ivory and his eyes round with content.

The other is the " last man "—not Montgomery's, but an earlier product — that man in gray, in a silk cap, and taking lazy whiffs at a cigar that has about crumbled to ashes. He is as calm as the Sphinx, but neither so grand nor so grim. He is going to San Francisco when—the train goes, and he patiently bides his time. He is an old traveler, and watches with an amused eye the human vortex. He has seen it before at Gibraltar, at Canton, and now at Omaha.

At last the conductor gives the word "All aboard!" signals the engineer who has been leaning with his head over his shoulder, the bell lurches from side to side with a clang, your last man gives his cigar a careless toss and swings himself upon the rear platform, and the train with its black banners and white flung aloft pulls out, and we are off for the plains and the deserts, and the gorges and the mountains, and the Western sea.

CHAPTER H. FROM VALLEY TO MOUNTAIN.

IF a man cannot stay at home, traveling in a Pullman palace car is the most like staying there of any-thing in the world. It takes about an hour to get settled in a train bound for a five days' voyage, and some people never do. See the man across the way. He has turned that carpet-bag over and over like a flapjack, and set it before him as a Christian does the law of the Lord, and had it under his feet, and tried to hang it up somewhere. It is as restless as a San Francisco flea. And then his overcoat has been folded with each side out, and his blanket vexes him, and his hat is an affliction, and he is a nephew-in-law of Martha, who was " troubled about many things." There is a sort of solar-system genius about some men in the adjustment of their rail-way belongings that is pleasant to see: everything with a sort of gravitation to it; all at hand and nothing in the way.

When people leave Omaha for the West they usually have eyes for nothing but the scenery. There was one man in our car who kept his nose in a book, like a pig's in a trough, and he had never traveled the route, and he was a tourist! An asylum for idiots ought to seem like home to him!

The sun was borrowed from an Easter-day. The air

is transparent. The willows show the green. The mean-der of emerald on the hillsides paints the route of the water-courses. We are overtaking the Spring. Behind us, Winter was begging at the door. The trees were as dumb as an obelisk. Around us are tokens of May and whispers of June. You are turning into a cuckoo —Logan's cuckoo; not General Logan, of the Boys in Blue, nor Logan, the last of his race, who used dolefully to say in the declamation of our boyhood, " not a drop of my blood flows in the veins of any living creature," but Logan the poet, who apostrophized the bird, " Companion of the Spring," and said:

"Sweet bird, thy bower is ever green, Thy sky is ever clear.

There is no sadness in thy song, No winter in thy year!"

We strike the bottom lands of Nebraska, as rich as Egypt. We are following the trail of Lewis and Clark, for here is a stream they christened Papilion, from the clouds of butterflies, those " winged flowers" that blossomed in the air as they went. The men are gone, but the breath of a name remains. Sixty miles from Omaha,

and no sign of wilderness. Towns, farms, rural honas

I confess to a covert feeling of disappointment. I expected to be knocked in the head with the hammer of admiration upon the anvil of sublimity right away. We have entered the great Valley of the Platte, the old highway of the emigrants, who paid fearful toll as they went. The world widens out into one of the grandest plains you ever be-held, and in the midst of it, lying flat as a whipped spaniel, is the Platte, a river that burrows sometimes like a prairie dog, and runs under ground like a mole,

30 BETWEEN THE GATES.

and sometimes broadens into a sea that can neither be forded or navigated — a river as lawless as the Bedouins. It would not be so much of a misnomer to rechristen it the Flat. And the thread of a train moves through this magnificent hall for hundreds of miles, with its sweeps of green and its touches of russet grass here and there, as if flashes of sunshine had rusted thereon in wet weather. Herds of cattle freckle the distance. An Indian village of smoky tents is pitched beside the track, and the occupants are all out, from the caliper-legged old grizzly to the bead-eyed papoose sprouting behind a squaw from " the fearful hollow " of his mother's dingy blanket. They are here to get the wreck of the lunch-baskets flung from the windows of the eastward trains. The chemistry of civilization has bleached some of them. It is a village of beggars.

Clouds fly low in the Valley of the Platte, and thunder-storms have the right of way. It was wearing toward sundown when great leaden clouds with white edges showed in the route of the train. They looked like -a solid wall with irregular seams of mortar, built up from earth to heaven. Then the wind came out of the wall, and the careening cars hugged the left-hand rail, and the hail played tattoo upon the dim windows, and the engine " slowed," for we were running in the teeth of the storm, and darkness fell down on the Valley like a mantle. The lightning hung all about in tangled skeins, like Spanish moss from the live-oaks, and played like shuttles of fire between heaven and earth, carrying threads of white and red, as if it were weaving a garment of destruction There were evidently but two travelers in the Valley, the storm and the train. And the thunder did not go

FROM VALLEY TO MOUNTAIN. 31

lowing and bellowing about like the bulls of Bashan, as it does among the Catskills and the Cumberlands, but it crashed short and sharp, like shotted guns, that have a meaning to them, and not like blank cartridges, " full of sound and fury, signifying nothing." The scene was sub-lime. The pant of the engine and the grind of the car-wheels were inaudible. We were traversing a battle-field. It was crash, rattle and flash. The " thunder-drum of heaven" must have had a drum-major to beat the long-roll that day.

There was a young lady in our car, California-born, who was returning home from an Eastern visit. She had never heard the thunder nor seen the lightning in all her life. She had lived in a cloudless land of everlasting serenity. The pedal-bass of the skies and the opening and shutting of the doors up aloft filled her with alarm, and when the storm died down to great fitful sighs, the lightest heart in all the train was her own.

We had hoped to see a prairie-fire somewhere on the way, if only it would not harm any body or thing—one of those flying artilleries of flame that sweep the plains in close order from rim to rim of the round world, but we were only indulged with a rehearsal. Just before the storm a fringe of fire showed in the Northwest, like an arc of the horizon in flames. It was as if Day, getting ready for bed, had trimmed it with a valance of fire; but it was "out," like Shakspeare's "brief candle," under the weight of the tempest.

We go to supper at Grand Island in sheets, like so many unbound books, albeit they were sheets of rain, and it was pleasant to get back to the lighted car, with its homelike groups and its summer hum of talk. Prepara-

tions for going to bed are in order. Sofas turn couches, and couches alcoves. The lean man shelves himself as •a saber is slipped into its scabbard. The fat man, condemned to the upper berth, is pulling himself up the side as an awkward bear boards a boat. There is a flitting of female shapes behind the restless curtains; one bulge in the crimson and the woman is unbuttoning her shoes; another bulge and she says, " Good-by, proud world, I'm going home," and she turns her back upon us and bounces into bed —"to sleep, perchance to dream."

The steady clank-it-e-clank of the wheels grows plain in the silence, like the roar below the dam of a village mill at night. There is something wonderfully sedative about the regular motion of the Overland Train. Its regular twenty and twenty-two miles an hour are as restful as a lullaby. There is no fatigue about it. The nervous dashes of a devil's-darning-needle of a train are as catching as the whooping-cough. They make you nervous also. As twenty-two miles is to forty-five miles, so is one worry to the other, is the Rule-of-Three of the road.

It is not usual for anybody to get up in the morning higher than he went to bed at night, but if you sleep from Grand Island and supper to Sidney and breakfast, you will have slept yourself more than two thousand feet higher than the sea level when you gave that pillow its last double and fell asleep.

The morning is splendid, and everybody is on the alert. "Prairie dogs!" cries some watchful lookout, and every window frames as many eager faces as it will hold. And there, to be sure, they are; the fat, rollicking, sandy dogs, as big as exaggerated. rats, but with tails of their own. They sit up straight as tenpins and watch the

FROM VALLEY TO MOUNTAIN. 33'

train. Their fore paws hang down from the wrists in a deprecating, mock-solemn way, as if they had just washed their hands of you, and said, " There they are; more of them; jogging along to California." They fling up a pair of heels and dive into their holes. They appear as much at home on one end as the other. Travelers say they bark at the. trains, but they didn't bark at ours, unless they "roared us gently." Soon there is another cry of "Antelope!" and again the car is in commotion. There the graceful fellows are, showing the white feather behind, as they dash off a little way, then turn and look at us with lifted head, then bound down the little hollows and out of sight. Prairie dogs and antelopes, in their native land, were better than two consolidated menageries at the East. To the tame passengers of the party, whereof this writer was one, there was a wilderness flavor about it quite strange and delightful. But there was a couple on board, a British lion and his mate, that never ventured an eye on

the picture. They were

Bible people, for " their strength was in sitting still," and in keeping still withal. The lion parted his hair in the middle, and his eyebrows were arched into the very Gothic of superciliousness. Escaped from the sound of Bow Bells, he was a cockney at large, and of all poultry

an exclusive cockney is the cheapest. The figure is a little mixed, but then there was a gallinaceous strain in

34 BETWEEN THE GATES.

his leonine veins. Together they made about as lively a brace of beings for the general company as a couple of mummies direct from the pyramid of Cephren would have been I respect the noble, hearty Briton of Motherland; I pray always that peace may dwell in her palaces—but the lion, in his best estate, is apt -to fall off a little in the hinder quarters. His front view is the grander view, but when those quarters are finished out before with the brow and bearing of a snob, it becomes an unendurable animal whose ancestors never would have been admitted into the Ark.

There is a mightier lift to the land. The bluffs and peaks begin to rise in the distance. The horizon is scolloped around as if some cabinet-maker had tried to dove-tail earth and sky together. To eyes that have looked restfully upon the rank green pastures of the East, these billowy sweeps of tawny landscape seem just the grazing that Pharaoh's lean kine starved upon, but they are really in about the finest grass country in America. Watch those dots on the hillsides at the right. They are sheep, and there are thousands if there is so much as one "Mary's little lamb." Those spots on the distant left, like swarms of bees, will develop, under the field-glass, into herds of "the cattle upon a thousand hills."

We are pulling up the world, and away to the North, like thunder-heads at anchor, rise the sullen ranges of the Black Hills, a glimpse or two of surly Alps. The first snow-shed is in sight. It looks like an old rope-walk slipped down the mountain on a land-slide, and we rumble through it while the unglazed windows wink day-light at us in a sinister way that is new, but not nice.

The first glimpse of Winter watching the world from

FROM VALLEY TO MOUNTAIN. 35

the crest of Colorado is a poem. There he stands in the clear Southwest, calm and motionless as Orion. Long's Peak is in sight! It seems near enough for a neighbor. It is eighty miles away. Its crown of snow is as serenely white in the sunshine as if there had been a coronation this very morning, and it had freshly fallen from the fingers of the Lord, and the height made King of the Silver State, the Centennial child of the Republic.

They say I shall see grander mountains, but that day and that scene will be bright in.my memory as the hour and the picture of perfect purity and peace.

I think of other eyes than mine—weary eyes—that brightened as they caught sight of that December in the sky. I think of the caravans of the long ago; of the heroes of the trail; of the oxen that swung slowly from side to side in their yokes, as if, like pendulums, they would never advance; of the days they traveled toward the Peak that never seemed to grow nearer, like a star in far heaven. And I see at the right of the train the old trail they wore, and the years vanish away, and the camp-fires of the cactus and grass are twinkling again, and I lie down beside them under the sky that is naked and strange, and I hear the cayote's wild cry and the alarms of the night.

An untraveled man's idea of a mountain is of a tremendous, heaven-kissing surge of rock, earth and snow, rolling up at once from the dull plain like a tenth wave of a breaker, and fairly taking your breath away. But a mountain range grows upon you gradually. It some-how gets under your feet before you know it, until the tingling sweep of the light air startles you with the truth that you are above the world.

36 BETWEEN THE GATES.

Here is an apparent plain, but in twenty miles you begin to encounter the globe's rough weather again. The tandem engines, panting and pulling together like a perfect match, labor up the Black Hills. The dimples of valleys are green as emeralds. The rugged heights are tumbled thick with gray granite, and sprinkled with dwarfs of pines that stand timidly about as if at a loss what to do next. A round eight thousand feet above the sea, where water boils with slight provocation, and you begin to feel a little as if you had swallowed a balloon just as they made ready to inflate it, and the process went on, and you are at Sherman. It is the highest altitude the engine reaches between the two oceans. Strange that the skill of a civil engineer can teach a locomotive how to fly without wings; can wile it up by zigzags and spirals along the craggy heights and through the air, fairly defrauding the attraction of gravitation out of its just due.

The train halted, and everybody disembarked, much as Noah's live cargo might have done on Ararat. We wanted to set foot on the solid ground at high tide like the sea, but we all discovered that it took a great deal of air to do a little breathing with. Nothing was disdained for a souvenir. Pebbles that little David would have despised were picked up and pocketed, and one of the party, more fortunate than the rest—it was the writer's alter ego—found a dainty little horseshoe on that tip-top of railroad things in North America, and bore it cheer-fully away— for doesn't it make us witch and wizard proof ? We accepted it as a good omen, but who wore it? Perhaps the winged horse, Pegasus, made a landing there and cast a shoe—if he was ever shod. Sherman

was named after the brilliant General who marched to the Sea.

Beyond the hemlock shadows of the spruce pine and the scraggy ridges, where giants played " jack-stones " when giants were, seventy miles away to the South, glitters Pike's Peak, whose name. was inked across many a canvas-covered wain in the old time, and whose cold and deathless light has kindled ardor in many a toiler's tired heart. Long's Peak, to the west of it, and three days'

journey off as the mules go, is near us still.

CHAPTER M.

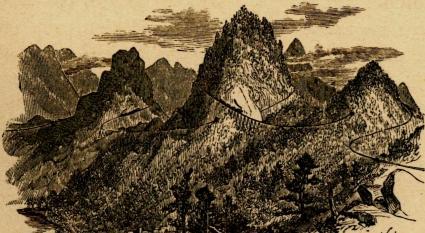

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CANON.

TO get away from great mountains in white cloaks is about as difficult as to escape from the fixed stars. We travel all day with ridges of snow on our left, billowing away into magnificent ocean scenery, as if the Arctic had been lashed into foaming fury, and then frozen to death with all its icebergs, drifts and caflons imperishable as adamant. They were thirty miles away, yet so distinct and clear-cut against the blue, so palpably present as seen through air that might blow on the plains of Heaven unforbidden, that almost anybody on the train fancied he could walk near enough to make a snowball before breakfast! This mountain atmosphere is a perpetual illusion. Among these gorges are those graceful cats with the long stride, to whom men are mice, the mountain lions—you will see a pair of them caged at the next station—and here are those huge but rather amiable and aromatic brutes, the cinnamon bears, the blondes among the bruins.

The train works its way between the Black Hills and the Rockies, and you half fancy, as you watch the silent plunge-down of their shaggy sides, and the gloomy gorges, and the inaccessible crags, that the grizzlies must have been born of mountains, not of bears. You can hardly realize that those monstrous dromedaries of hills, those

38

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CANON. 39

stone mastodons lying about, with streaks of Winter here and there, really belong to the backbone of the continent.

Among those sombre hills the thunders have their nests, and when the broods come off, as they do sometimes, five at once, the flapping of their wings is something to be remembered. Think of five thunder-storms let loose in the air together, all distinctly outlined like men-of-war!

Nature has its compensations, and so you are not surprised to know that rainbows are about two fingers broader here than they are in the East, and the colors deeper and brighter. There is no lack of material for making those gorgeous old seals of the covenant. But I did not see enough ribbon of a bow to make a girl's necktie, nor hear thunder enough to stock a Fourth-of-July oration.

Before setting out for the Golden Coast, I thought a young earthquake would be pleasant to write about, and there is the Bohemian instinct. I have changed my mind. People who are acquainted with them tell me that no-novice needs an introduction when he experiences one of those planetary ague-thrills. He knows it as well as if he had been rocked in the same cradle and brought up with an earthquake all his life. It jars his ideas of earthly stability all to pieces. Who is it says that the globe is swung by a golden chain out from the throne of God, and that sometimes a careless angel on some errand bound, just touches that chain with the tip of his long wings, and it vibrates through all its links, and so we have the little shiver men call earthquake? I fancy that writer regarded the phenomenon through the long-range telescope of sentimental poetry. "Let us have peace."

BETWEEN THE GATES.

The tribes and nations of bright-hued flowers every-where are wonderful to behold. No chasm so dark, no mountain so rude, that these fearless children of Eden are not there. They smile back at you with their quaint faces from rugged spots where a Canada thistle would have a tug for its life. They ring blue-bells at you. They salute you with whole belfries of pink and purple chimes. They swing in delicate necklaces from grim rocks. They flare like little flames in unexpected places. You see old favorites of the household magnified and glorified almost beyond recognition. It is as if a poor little aster should full like the moon and be a dahlia. The inmates of the Eastern conservatories are running about wild, like children freed from school. And it does not look effeminate to see a broad-breasted, wrinkled rock with a live posy in its button-hole. I think every human bosom, however rude and rough, has some sweet little flower of thought or memory or affection that it wears and cherishes, though no man knows it. Let us have charity.

Hark! There is nothing to hear! The engines run as still as your grandmother's little wheel with her foot on the treadle. The tandem team is holding its breath a little. It is not exactly facilis est deseensus Averni, but in plain talk we are going down hill. We are making for the Laramie Plains. They open out before us into four thousand square miles of wild pasture. They sweep from the Black Hills to the range of the Medicine Bow. Where are your Kohinoors, your " mountains of light," now? Yonder are the gorgeous Sultans, the Diamond Peaks cut by the great Lapidary of the Universe. And yet they may be tents, those radiant cones, pitched by

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CARON. 41

celestial shepherds on that lofty height. Did ever earthly pastures have such regal watch and ward? See there, away beyond the jeweled encampment, where the Snowy Range lifts into the bright air, as if it were a ghostly echo of the Diamond Peaks at hand.

All the country is rich in mineral wealth as a thou-sand government mints. The Bank of England, " the Old Lady of Threadneedle street," could lay the very foundations of her building upon a specie basis should she move it hither. Those suspicious holes far up the mountain sides and away down in the valleys, with their chronic yawn of darkness, are not the burrows of bears nor the dens of beclawed and bewhiskered creatures that make night hideous with complaint. They are the entrances to mines of gold, silver, copper, lead and cinnabar. Cinnabar is the red-faced mother of white quicksilver, but she has a ruddy daughter that inherits the family complexion. You have seen her on sweeter kissing places than these rude mountain heights. She shows at times upon a woman's cheek, and her name is Vermilion.

You see all along, ruined castles, solitary towers, triumphal columns, dismantled battlements, broken arches, some red as with perpetual sunset, and some gray with the grime of uncounted years. At the mouth of that caflon, far up the crags, stands a Gibraltar of desolation, a speechless city where no smokes pillar to the skies, no wheels jar the rocky streets, no banners float from minaret or dome. It is the city of No-man's-land. Its builders are the volcanic blacksmiths. How the forges roared and glowed to make it! Its sculpture is the work of frost and rain and time. It has been founded a thou-sand years.

2*

42 BETWEEN THE GATES.

The coarse bunches of buffalo grass dot the plains here and there. A mule would carry his ears at "trail arms" if it were offered him for breakfast, but it is sweet to the raspy tongues of the beef-cattle of the wilderness. It is the buffalo's correlative: first the grass, then the beast. Where are the stately herds, fronted like the curly-headed god of wine or the Numidian lion, that in columns myriad strong trampled out ground-thunder as they marched? Gone to gratify the greed of lawless butchers who turned a ton of beef into a vulture's dinner for the sake of a dozen pounds of tongue. Cowper's man who shot the trembling hare was a prince to such fellows.

Sage-brush has the freedom of the desert, highland and lowland. You see its clumps of green everywhere. It is the rank seasoning, the summer-unsavory for the sage-hen. Though without beauty, you regard it with affection. It was the fuel of the old pioneers. It has cooked the buffalo-steak, and boiled the coffee, and baked the wheaten cake. Women with babes in their arms have gathered around the sage-brush fire in the chill nights and thanked God. Strange, indeed, that the more we receive the more ungrateful we grow! And there are the cactuses, the green pincushions of the desert, the points all ready to the heedless hand.

By Point of Rocks, where stand the columns of the American Parthenon, four hundred feet high, a thousand feet in the air, and grander than any Grecian ruin that ever crumbled; over Green river, lighted up by its fine green shale McAdam as an old pasture brightens in May; through clefts where rock and ridge run riot; sunless gorges where crags frown down upon the train from the top of the sky; swinging from cliff to cliff, as spiders float

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CANON. 43

on their flying bridges; booming through snow-sheds, with their flitter of sunshine; on tracks looped around upon themselves like love-knots for Vulcan; railroad above you and railroad below; by giants' clubs, and bishops' mitres, and Cleopatra's Needles, and Pompey's Pillars, and monoliths of Pyramids older than Cheops, founded with a breath and builded with a touch; up on the swell and down in the trough of the boisterous old mountains, as a ship rides the sea; past the mouths of grim canons that swallow the day; through tunnels of midnight that never knew dawn; cutting flourish and capital, swings the long, supple train.

Through a gate in the Wahsatch Mountains we plunge into Echo Canon and Utah together; Utah, the tenth sovereignty on our route from New York; Utah, Turkey the second, and the land of harems—much as if you should bind up a leaf or two of the Koran with the books of Moses — a region where the Scripture is reversed, and one man lays hold of seven women. You look to see the red fez and the Turkish veil, and you do see dwellings with a row of front doors that seem to have been added, one after another, as the new brides came into the family; a door a bride, which is pretty much all the adoration any of the poor creatures get.

Yonder, in a row before a house with three doors, sit a man and three women, and around them a group of children of assorted lengths, like the strings of David's harp. Here, for the first time, I see a Mormon store with its sanctimonious sign. It almost seems to talk through_ its nose at you with the twang that often issues from an empty head and seldom from a full heart, and it whines these words: "Holiness to the Lord"—here the picture

44 BETWEEN THE GATES.

of an eye—"Zion's Co-operative Mercantile Institution," and the profits of it are the prophet's, and his name was Brigham Young.

The train is just swinging around a bold battlement of rock, beside which Sir Christopher Wren's St. Paul's would be nothing more than the sexton's cottage. You see at its base a well-worn wagon-road, that looks enough like a bit of an old New York thoroughfare to be an emigrant. It is the stage road and trail of the elder time. You catch a glimpse of irregular heaps of stone piled upon the edge of the precipice five hundred feet aloft. They are the solid shot of the Mormon artillery. Twenty years ago, when the United States troops were marching to Salt Lake, with inquisitive bayonets, curious to know whether the Federal Government included the heathendom as well as the Christendom of the United States, they must pass by that rugged throat of a road, and under the frown of the mountain, and here the Nauvoo Legion proposed to crush them with a tempest of rock, but the army halted by the way and the ammunition remains.

The train seems hopelessly bewildered. It makes for a mountain wall eight hundred feet high, just doubles it by a hand's-breadth, sweeps around a curve, plunges into a gorge that is so narrow you think it must strangle itself if it swallows the train; red rocks everywhere huge as great thunder-clouds touched by the sun, and big enough for the kernel of such a baby planet as Mars; monuments, graven by the winds; terraces, along whose mighty steps the sun goes up to bed; the glow of his crimson sandal on the topmost stair, and it is twilight in the valley and midnight in the gorge. It is a fearful

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CANON. 45

nightmare of stone giants. Weird witches in gray groups, whispering together in the hollow winds of the mountains; witches' bottles for high revel; Egyptian tombs; fortresses that can never be stormed. Yonder, a thousand years ago, they were launching a ship six hundred feet high in the air, but it holds fast to " the ways" still ! Its stately red bow carries a cedar at the fore for a flag. It is a craft without an admiral. Some day an earth-quake out of business will turn shipwright, put a shoulder to the hull, and leviathan will be seen no more.

If you want to reduce yourself to a sort of human duodecimo, handy to carry in the pocket, you can effect the abridgment as you make the plunge with bated breath into the canon. It is a splendid day, old Herbert's sky above and a Titanic carnival below. Echo Canon, where voices answer voice from cliff and wall and chasm, and talk all around the jagged and gnarled and crushed horizon. Just the place for Tennyson's bugle;

"The splendor falls on castle walls, And snowy summits old in story—"

and here is Castle Rock, with its red lintels and its gray arches, and the mighty Cathedral that no man has builded, with its sculptures and its towers; and yonder is the Pulpit, ten thousand tons of stone heaved up a hundred feet into the air, where Gog and Magog might stand and be pigmies; and there are the white lifts of the Wahsatch Range:

"The long light shakes across the lakes,

And the wild cataract leaps in glory. Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying, Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying.

"0, hark, 0 hear! how thin and clear, And thinner, clearer, farther going!

46 BETWEEN THE GATES.

0, sweet and far from cliff and scar The horns of Elfland faintly blowing!

Blow, let us hear the purple glens replying:

Blow, bugle; answer, echoes, dying, dying, dying—"

and here are glen and cliff, and here is Elfland. The engine gives a single scream, and airy trains are answering from crag and crown, from gulf and rock, as if engines had turned eagles and taken wing from a hundred mountain eyries.

"0 love, they die in you rich sky,"

and here is that same sky above us, affluent with the flowing gold of the afternoon sun; an unenvious sky that lets you look through into heaven itself; an ethereal azure like the glance of a blue-eyed angel;

"They faint on hill, on field, on river;"

and here beside us the Weber River rolls rejoicing, and the hills are not casting their everlasting shadows upon us like the veil of the temple that could not be rent. And then come the last lines, that, thanks unto God, are true the world over:

"Our echoes roll from soul to soul,

And grow forever and forever.

Blow, bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying,

And answer, echoes, answer, dying, dying, dying."

Let the lyric be known as the Song of Echo Canon. In my memory the twain will be always one.

This being afraid of a motionless rock when -there is no more danger of its falling than there is of the moon crushing your hat in, is a new feeling, and yet it is an emotion akin to fear. So vast, so rude, so planetary in magnitude, such ghostly and ghastly and unreal shapes, you fancy some enchantment holds strange beings locked

WONDERLAND TO BUGLE CARON. 47

in stone; that, some day, there will be a general jail-delivery, and the spell will be broken. To me, as I re-member that valley of illusions, they seem the monstrous petrifications of a wild and riotous imagination. I am glad I saw that huge stoneyard of the gods, but I have no desire, to dwell in it. To have heard a bugle blown in it would have been something to remember, but I should have wanted it to sound " boots and saddles," and then be the first man to mount. To carry those boulders about mentally requires an atlas of a fancy, so I will just leave them where I found them, monuments to the memory of patient centuries and imperishable power. Weber River and the Pacific train are both doing their best to get out of these enchanted mountains, but they stand before us, and close up behind us, and draw in around us, and offer us gorges to hide in, and water to drown in, and gulfs to tumble in, and anvils to dash our brains out, and—there! the escape is accomplished! The rugged canon vanishes like a dream of the night, and a valley of surpassing loveliness, sweet as the vale of Rasselas or Avoca, a little parlor of the Lord, guarded by gentle mountains and carpeted with the fine tapestry of cultivation, and dwelt in by peace, has taken. us in. Have you ever, when walking along a woodland path in s, summer night, discovered a dewdrop at your feet by the light of a star that shone in it? So is that valley, fallen amid those scenes of ruggedness and wonder.

CHAPTER IV.

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN.

" THE Thousand-mile Tree!" So cried everybody.

There it stands beside the track, with its arms in their evergreen sleeves spread wide in perennial greeting. A thousand miles from Omaha and twenty-five hundred from New York. No stately tree with a Mariposa ambition, yet, after the Oak of the Charter and the Elm of the Treaty, few on the continent are worthier of historic fame. Forty years ago, defended round about by two thousand miles of wilderness, a wilderness as broad as the face of the moon at the full ! To-day it is almost like the tree of knowledge, " in the midst of the garden." The articulate lightnings run to and fro upon their single rail, almost within reach of its arms, from Ocean to Ocean. Hamlets and cities make the transit of the wilderness like Venus crossing the sun. Millions of eyes shall look upon it with a sentiment of affection. It stands in its vigorous life for the Thousandth Milepost on the route of Empire.

Why so many grand things in the Far West go to the Devil by default nobody knows. I think it high time he proved his title. Thus, " Devil's Gate " names a Gothic pass in the cleft mountains, through which, between rocky portals lifting up and up to the snow-line, the mad and crested waters of the Weber River plunge in tumultuous crowds. They seem a forlorn hope storm-

48

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN. 49

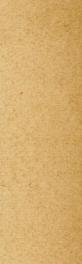

ing some tremendous Ticonderoga. " The Devil's Slide " is a Druidical raceway seven hundred feet up on the mountain side, twelve feet wide, pitched at an angle of

fifty degrees, and dry as a powder-house. It is bounded

by parallel blocks of granite lifted upon their edges, and projecting from the mountain from twenty to forty feet. A ponderous piece of work, but who was the stone-mason? Instead of being a slide, it seems to me about such a

THOUSAND-MILE TREE.

pig-trough as Cedric the Saxon would have hewn, in the days before "hog" turned "pork" and "calf" was " veal." If it belongs to the Devil at all, it must have been the identical table-ware he pitched after the herd of possessed swine that ran down into the sea, and here it lies high and dry even until this day.

At Ogden we take the Silver Palace-cars of the Central Pacific. Let nobody forget what toil, danger, privation, death and clear grit it cost to bring the twenty miles an hour within human possibilities; that everything from a pound of powder and a pickax to a railroad bar

3

50 BETWEEN THE GATES.

followed the track of the whalers of old Nantucket and doubled Cape Horn; a hundred miles and a lift of seven thousand feet heavenward; a hundred miles and not a drop to drink for engine or engineer; a thousand miles and hardly an Anglo-Saxon dweller. Two thousand feet of solid granite barred the way upon the mountain top where eagles were at home. The Chinese Wall was a toy beside it. It could neither be surmounted nor doubled, and so they tunneled what looks like a bank-swallow's hole from a thousand feet below. Powder enough was expended in persuading the iron crags and cliffs to be a thoroughfare to fight half the battles of the Revolution. It was in its time the topmost triumph of engineering nerve and skill in all the world. It stitched the East and the West lovingly together, and who shall say that we are not a United States?

The level rays of the setting sun glorified the scene as we steamed out a- few miles, until at our left, a sea of glass, lay the Great Salt Lake, a fishless sea, and as full of things in " urn" as an old time Water Cure used to be of isms, with its calcium, magnesium and sodium. A man cannot drown in it comfortably. No decent bird will swim in it. If Jonah, the runaway minister, had been pitched into it, that lake would have tumbled him ashore before he had time to take lodgings at the sign of " The Whale." It absolutely rejects everything but some-thing in " um." It ought to be the " duke dons um " for Lot's wife. Everybody passes Promontory Point in the night, the memorable spot where, on that May day, 1869, the East and the West were wedded, and the blows that sent home the spikes of silver and gold securing the last rail in the laurel were repeated by lightning at Wash-

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN. 51

ington and San Francisco, in the length of a heart-beat; blow for blow, from the Potomac to the Pacific. Think of echo answering echo through a sweep of more than three thousand miles! All in all, after the signing of the Declarationtof Independence, it was the most impressive and thoughtful ceremony that ever graced the continent. It was electric with the spirit of the New Era.

Tally Eleven! We are in Nevada, eleventh sovereignty from the Atlantic seaboard. We have struck the Great American Desert. I wish I could give, with a few brief touches, the scenery of the spreads of utter desolation, strangely relieved by glimpses of valleys of clover that smell of home, and conjure up the little buglers of the dear East, that in their black and buff trimmed uniforms and their rapiers in their coat-tail pockets, used to campaign it over the fields of white clover where we all went Maying; sights of little islands of bright greenery, as at Humboldt, as much the gift of irrigation as Egypt is of the Nile; great everlasting clouds of mountains, tipped as to their upper edges with snow as with an eternal dawn; patches ghastly white with alkali as if earth were a leper, and yellow with sulphur as if the brimstone fire of the Cities of the Plain had been raining here, and salt had been sown and the ground accursed forever.

Tumble in upon these alkali plains a few myriads of the buffalo that have been wantonly slaughtered, and with the steady fire of the unwinking, unrelenting, lid-less sun that glares down upon the dismal scene as if he would like to stare it out of existence, you would have the most stupendous soap factory in the universe, to which the establishments of the Colgates and the Babbitts would be as insignificant as the little inverted conical

52 BETWEEN THE GATES.

leach of our grandmothers, wherewith they did all the lyeing the dear simple souls were guilty of.

Fancy an immense batch of wheaten dough hundreds of miles across, wet up, perhaps, before Columbus discovered America, permeating and discoloring and tumefying in the sun through five centuries; strown with careless handfuls of salt and sprinkles of mustard, and garnished, like the mouth of a roasted pig, with parsley-looking sage-brush, and tufts of withered grass, and rusty cactuses, and veins of dead water sluggish as postprandial serpents; and whiffs of hot steam from fissures in the unseemly and ill-omened mass; a corpse of a planet weltering and sweltering, with whom gentle Time has not yet begun; no May to quicken it, no June to glorify it, no Autumn to gild it.

Then fancy all this in a huge basin whose red and rusty rim, broken and melted out of shape, you see here and there in the northern horizon—fancy all this, and yet there is nothing but " the sight of the eyes" that will " affect the heart." Miners and mountain men have been lavishly liberal in giving things to the Devil. If he must have something in the way of estate, give him this bleached batch of desert dough for his own consumption!

You will take notice that in this description of waste places I have not mentioned Tadmor nor alluded to Thebes. A man cannot very well be reminded of things he never saw; neither have I quoted anything from Ossian about lonely foxes and disconsolate thistles waving in the wind. All these things have been mentioned once or twice, and the American Desert needs no foreign importations of Fingals to make it poetically horrible.

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN. 53

You nave gone over it in a palace. You have eaten from tables that would be banquets in the great centres of civilization. You have slept upon a pleasant couch " with none to molest or make you afraid." You have drank water tinkling with ice like the chime of sleigh-bells in a winter night—water brought from mountains fifteen, twenty, thirty miles away. You have retired without weariness and risen without anxiety. Now, I want you to remember the men and women without whom there would be nothing worth seeing that could be seen, on the Pacific Slope; the men and women who crossed these plains in wagons whose very wheels clamored for water as they creaked; those men and women who toiled on through this realm of disaster, parched, famished, dying yet not despairing, to whom every day was only another child of the Summer Solstice, and who said every morning, " Would to God it were night!" Some made their graves by the way, and some lived to look upon the Pacific sea, and I want you to believe that in our time there has never been a sturdier manhood, a ruggeder resolution, a more Miles Standish sort of courage, than marked the career of the pioneers to the West.

Tally Twelve! Twelfth empire from the Atlantic. Less than three hundred miles from the Pacific. We are in California—the old Spanish land of the fiery furnace. The turbaned mountains rise to the right, and the dark cedars and pines in long lines single file, like Knight Templars in circular cloaks, seem marching up the heights.

You feel, somehow, that though not a pine-needle vibrates, the wind must be " blowing great guns," so to

54 BETWEEN THE GATES.

ruffle up and chafe the solid world. Across ravines that sink away to China like a man falling in a nightmare, and then the swooning chasms suddenly swell to cliffs and heights gloomy with evergreens and bright with Decembers that never come to Christmas, the train pursues its assured way like a comet. It circles and swoops ,and soars and vibrates like a sea-eagle when the storm is abroad. Mingled feelings of awe, admiration and sublimity possess you. Sensations of flying, falling, climbing, dying, master you. The sun is just rising over your left shoulder. It touches up the peaks and towers of ten thousand feet, till they seem altars glowing to the glory of the great God. You hold your breath as you dart out over the gulfs, with their dizzy samphire heights and depths. You exult as you ride over a swell. Going up, you expand. Coming down, you shrink like the kernel of a last year's filbert. We are in the Sierras Nevada! The teeth of the glittering saws with their silver steel of ever-lasting frost cut their way up through the blue air—up to the snow-line—up to the angel-line between two worlds.

It was day an instant ago, and now it is dark night. The train has burrowed in a tunnel to escape the speech-less magnificence. It is roaring through the snow-sheds. It is rumbling over the bridges. Who shall say to these breakers of sod and billows of rock, " Peace, be still!" and the tempest shall be stayed and the globe shall be at rest?

And all at once a snow-storm drives over your head. The air is gray with the slanting lines of the crazy, sleety drift. Some mountain gale that never touches the lower world, but, like a stormy petrel, is forever on the

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN. 55

wing and never making land, has caught off the white caps and turbans from some 'ambitious peaks, and whipped them whirling through the air. You clap your hands like a boy, whose sled has been banging by the ears in the woodshed all summer, at his sight of the first snow. But the howling, drifting storm goes by, and out flares the sun, and the cliffs are crimson and silver.

You think you have climbed to the crown of the world, but lo, there, as if broke loose from the chains of gravitation, "Alps on Alps arise." Look away on and on, at the white undulations to the uttermost verge of vision, as if a flock of white-plumed mountains had taken wing and flown away.

A chaos of summers and winters and days and nights and calms and storms is tumbled into these gulches and gorges and rugged seams of scars. , Rocks are poised midway gulfward that awaken a pair of perpetual wonders: how they ever came to stop, and how they ever got under way. With such momentum they never should have halted: with such inertia they never should have

56 BETWEEN THE GATES.

started. Great trees lie head-downward in the gulfs. Shouting torrents leap up at rocky walls as if they meant to climb them. See these herds of broad-backed recumbent hills around us, lying down like elephants to be laden. See the bales of rocks and the howdahs of crags heaped upon them. They are John Milton's own beasts of burden, when he said, " elephants endorsed with towers," and such an endorsement should make anybody's note good for a million.

Do you remember the old covered bridges that used to stand with their feet in the streams like cows in mid-summer, and had little windows all along for the fitful checkers of light? Imagine those bridges grown to giants, from five hundred to two thousand feet long, and strong a a fort. Imagine some of them bent into immense curves that, as you enter, dwindle away in the distance like the inside of a mighty powder-horn, and then lay forty-five miles of them zigzag up and down the Sierras and the Rockies, and wherever the snow drifts wildest and deepest, and you have the snow-sheds of the mountains, with-out which the cloudy pantings of the engines would be as powerless as the breath of a singing sparrow. They are just bridges the other side up. They are made to lift the white winter and shoulder the avalanche. But you can hardly tell how provoking they are sometimes, when they clip off the prospect as a pair of shears snips a thread, just as a love of a valley or a dread of a canon, or something deeper or grander or higher or ruder catches your eye, " Out, brief candle ! " and your sight is extinguished in a snow-shed. But why complain amid these wonders because you have to wink!

Summit Station is reached, with its sky parlors, and

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN. 57

grand Mount Lincoln, from whose summit it is two miles "plumb down" to the city by the sea, and we have a mile and a half of it to swoop. The two engines begin to talk a little. One says, " Brakes!" and the other, "All right!" " Take a rest!" says the leader. " Done ! " says the wheeler, and they just let go their nervous breaths, and respire as gently as a pair of twin infants. The brakes grasp the wheels like a gigantic thumb and finger, the engines hold back in the breeching, but down we go, into the hollows of the mountains; along craggy spines, as angry as a porcupine's and narrow as the way to glory; out upon breezy hills red as fields of battle; off upon Dariens of isthmuses that inspire a feeling that wings will be next in order. Sparks fly from the trucks like fiery fountains from the knife-grinder's wheel, there is a sullen Bride of expostulation beneath the cars, but down we go. Should the water freeze in the engines' stomachs, " the law that swings worlds would whirl the train through ! "

The country looks as if a herd of mastodons with swinish curiosity had been turned loose to root it inside out. It is the search for gold. Mountains have been rummaged like so many potato-hills. When pickax and powder and cradles fail, and the " wash-bowl on my knee" becomes what Celestial John talks—broken China —then as yonder! Do you see those streams of water playing from iron pipes upon the red hill's broad side? They are bombarding it with water, and washing it all away. The six-inch batteries throw water about as solid under the pressure as cannon-shot. A blow from it would kill you as quick as the club of Hercules. Boulders dance about in it like kernels in a corn-popper. I give

58 BETWEEN THE GATES.

the earnest artillerymen a toast: "Success to the douche! The heavier the nugget the lighter the heart."

The train is swaying from side to side along the ridges, like a swift skater upon a lake. It is four thousand feet above the sea. It shoulders the mountains to the right and left. It swings around this one, and doubles back upon that one like a hunted fox, and drives bows-on at another like a mad ship. Verily, it is the world's high-tide! You have been watching a surly old giant ahead. There is no climbing him, nor routing him, nor piercing him; but the engines run right on as if they didn't see him. Everybody wears an air of anxious expectancy. We know we are nearing the spot where they let men down the precipice by ropes from the mountain-top, like so many gatherers of samphire, and they nicked and niched a foothold in the dizzy wall. and carved a shelf like the ledge of a curved mantel-piece, and scared away the eagles to let the train swing round.

The mountains at our left begin to stand off, as if to get a good view of the catastrophe. The broad canons dwindle to galleries and alcoves, with the depth and the distance You look down upon the top of a forest, upon a strange spectacle. It resembles a green and crinkled sea full of little scalloped billows, as if it had been overlaid with shells shading out from richest emerald to lightest green. Nature is making ready for something. The road grows narrower and wilder. It ends in empty air There is nothing beyond but the blue! And yet the engines pull stolidly on.

Down brakes! We have reached the edge of the world, and beyond is the empyrean! You stand upon

THE DESERT, THE DEVIL AND CAPE HORN. 59

the platform. The engines are out of sight. They are gone. The train doubles the headland, halts upon the frontlet of Cape Horn!— clings to the face of the precipice like a swallow's-nest.

The Grand Canon is beneath you. It opens out as with visible motion. The sun sweeps aslant the valley like a driving rain of gold, and strikes the side of the mountain a thousand feet from the base. There, twenty-five hundred feet sheer down, and that means almost a half mile of precipice, flows in placid beauty the American River. You venture to the nervous verge. You see two parallel hair-lines in the bottom of the valley. They are the rails of a narrow-gauge railroad. You see bushes that are trees, martin-boxes that are houses, broidered handkerchiefs that are gardens, checked counterpanes that are fields, cattle that are cats, sheep that are prairie-dogs, sparrows that are poultry. You look away into the unfloored chambers of mid-air with a pained thought that the world has escaped you, has gone down like a setting star, has died and left you alive ! Then you can say with John Keats upon a far different scene, when he opened Chapman's magnificent edition of Homer:

"Then felt I like some watcher of the skies When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes He stared at the Pacific, and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise—Silent upon a peak in Darien."

Queer people travel. Returning to the car I saw a broad-gauge Teuton, with the complacent bovine expression of a .ruminating cow, eating a musical Bologna lunch of " linked sweetness long drawn out," and I said to him, " Did you see Cape Horn?" " Cabe Hornd? Vat

60 BETWEEN THE GATES.

is she?" One of those difficult old-bachelor questions that will never find anybody to answer. Everything in this world but sausage and lager

"A yellow primrose was to him, And it was nothing more."

ACALIFORNIA train is a human museum. Here now, upon ours, are the stray Governor of Virginia, an army captain going to his company in Arizona, a trader

from the Sandwich Islands, a woman from New Zealand, a clergyman in search of a pastorate, an invalid looking for health, a pair of snobs, Mongolians with tails depending from between their ears, the proprietor of an Oregon salmon-fishery, a gold-digger, a man whose children were born in Canton while his wife lived in San Francisco, some Shoshones and dogs in the baggage car, and a family who ate by the day, breakfasted, dined, supped, lunched, picked and nibbled without benefit of clergy. It would take a chaplain in full work just to "say grace" for that party_ Victuals and death were alike to them. Both had " all seasons for their own." They ate straight across

the continent. If they continue to make grist-mills of

themselves, crape for that family will be in order at an early day.

At some station in the Desert where we halted for water, there sat, huddled upon the platform, some Shoshone Indians, about as gaudy and filthy as dirt and red blankets could make them, and papooses near enough like little images of Hindoo gods to be cousins to the whole mythology. One of the squaws, with an ashen

61

62 BETWEEN THE GATES.

gray face and white hair, a forehead like a hawk's, an eye like a lizard's, an arm like a ganglion of fiddle-strings, and a claw of a hand, looked to be a hundred years old, and her voice was as hollow as if she had an inverted kettle for the roof of her mouth, and talked under it. Near by, on the same platform, an English-man was pacing to and fro, putting down his well-shod feet as if he had taken the country in the name of the queen of 'ome and the Empress of India. A Frenchman, in a round cap with a tassel to it, stands with the wind astern and his brow bent like a meditative Bonaparte, trying to light a twisted roll of paper in the hollow of his hand. Two Chinamen in blue, broad-sleeved blouses, their shiny black cues swinging behind like bell-ropes in mourning, stood near, shying their ebony almonds at the whole scene. On the track, waiting for a shake of the bridle, waited the engine, breathing a little louder 'low and then, like a man turning over in his sleep.